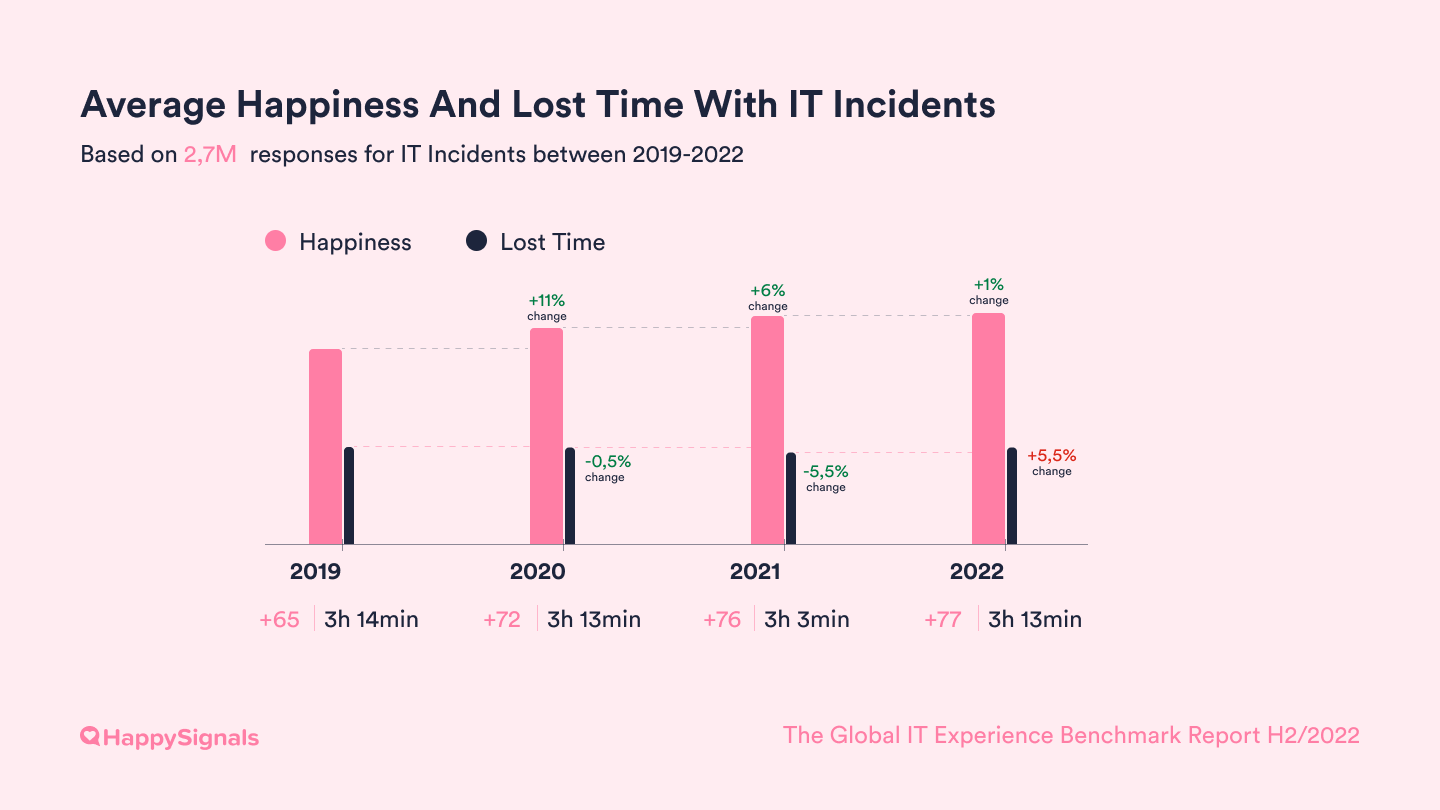

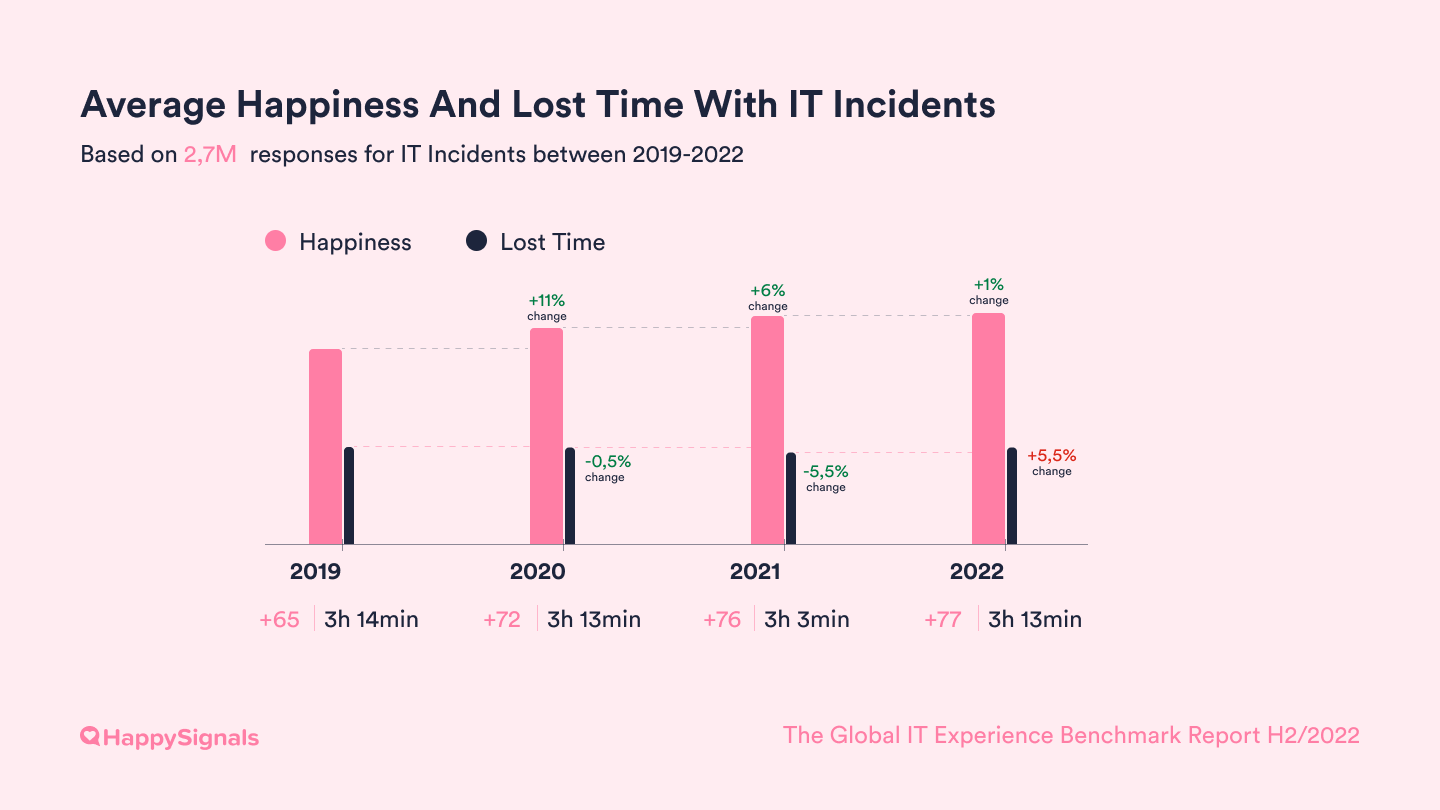

According to The Global IT Experience Benchmark H2/2022, employees perceived their lost time as 3 hours and 13 minutes (3.22 hours) per IT incident. The lost time statistic has been relatively consistent since 2019:

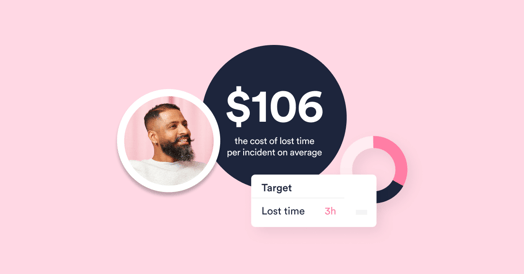

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that average hourly earnings for US workers in private industry for December 2022 totaled $32.92 per hour. Putting these statistics together tells us that the cost of lost time per incident is, on average, $106 (3.22 X $32.92) in the US. MetricNet benchmarking data tells us that in organizations, users experience an average of roughly one incident per month, variable by industry.

Meanwhile, we may still be cruising along blissfully, thinking that "doing more with less" in our IT support group will be enough. It's not. Actual cost savings come from improvement in the overall IT environment, not budget-cutting by the service desk. The usual fully burdened cost-per-ticket metric—still being touted as the "ultimate service desk metric" by many, gives only a small slice of the financial picture. It's a siloed, inside-out view.

Let us consider the XYZ Company, which has 5,000 employees. That's roughly 5,000 IT incidents per month, according to the MetricNet statistic. The fully burdened cost per service desk ticket is about $25 across the industry (and much more for desktop/deskside support).

Cost per Ticket: 5,000 incident tickets X $25 = $125,000 per month, or $1,500,000 per year

If, however, we look at it from the point of view of the entire organization and not just the service desk, the cost is astronomically higher.

Cost of Lost Time: 5,000 incidents X 3.22 hours each = 16,100 hours per month

16,100 hrs. X $32.92 per hour = $530,012 per month, or $6,360,144 per year.

You can't afford it

That $6.36M is not in the IT budget. It's not in any XYZ company budget. It's operating expense (OpEx) distributed across the company, and nobody knows where that money goes unless they are looking at the data on lost time. If we say with Benjamin Franklin, "Time is money," we should also say Lost time is lost money. To put it bluntly, no amount of cost-cutting by the service desk will make up for the money that is spent, year after year, because of the lost productivity caused by IT incidents.

It's important to say that this is not the cost of downtime. Gartner defines downtime as "The total time a system is out of service." The cost of downtime includes lost revenue—for example, the massive Facebook outage of 2021, which cost the company over $60 million. The incidents we're discussing here may be associated with downtime, but we're looking at it from the perspective of lost productivity. After a major incident of the sort Facebook suffered, an investigation into the causes and (hopefully) a plan to prevent such losses emerges.

Meanwhile, companies (and other types of organizations) are absorbing substantial losses that are not examined. No one does a root cause analysis when Chris's Salesforce access is broken, for example, or Pat's laptop won't boot up. Yet, productivity is lost, and the money vanishes.

You can't argue it

Some will argue that if it takes IT an hour to fix Pat's laptop, how does Pat report over three hours of lost time? To put things in perspective, let's step out of IT and into the world of having a home. Let's say I have planned to spend Saturday doing yardwork and want to start the morning by mowing my lawn. The lawnmower won't start, even after I spend 25 minutes trying, after which I spend almost 40 minutes digging out the owner's manual and troubleshooting the mower. I then spend 15 minutes contacting the local mower repair shop and arranging to have a service visit. So far, I've spent 80 minutes (one hour and 20 minutes) and haven't gotten the lawn mowed or anything else.

Now I move on to cutting down a rose bush. While I'm cutting down the rose bush, the mower repair person appears and gets my mower started. But before I mow, I finish cutting the bush and haul the cuttings away. Now I need a bit of a break, so I sit down in the shade and drink some lemonade before I return to mowing. Oh—and before I mow, I start the mower a few times to ensure it works.

Likewise, Pat tried over and over to get the laptop booted up, checked the power connection, checked the battery charger, looked at the manual, and used a smartphone to look at some knowledge articles about the laptop issue, knowing full well the service desk would ask whether these things had been done. Time slips away, Pat reports the issue and moves on to tasks that don't require the laptop while waiting for a fix from IT. Pat, by the way, does not have an on/off switch; it takes time to switch tasks.

According to multiple studies, refocusing takes 23 minutes or more after an interruption. That's 23 minutes (.383 hours) at $32.92 per hour or $12.61 just in refocusing time. The employee reports their lost time from when the issue occurs until they are back on plan and in their workflow. We're not measuring machine performance; we're measuring people's experience. 23 minutes to refocus on another task after the interruption, and 23 minutes to refocus on the original work after the laptop is up and running again. Now that 3 hours and 13 minutes doesn't seem unreasonable, does it?

You can't sit and do nothing about it

Now that we understand the true financial ramifications of IT incidents, what do we do about them? We look for ways to improve so that we're reducing these. But where do we start? ITXM™ data can be of enormous assistance here as well. This article, Focusing Your Continual Improvement Investments Through the Lens of Experience, says it can help us:

- Focus on the right things

- Succeed in making the improvements people want (and need)

- Reach the level of happiness and productivity employees desire

- Steer our efforts in the right direction.

If you want to control your costs, you must focus on costs across the entire organization and make improvements based on what you learn. Experience data is of enormous value to both of these.

To learn how the HappySignals platform helps, see here.

View a webinar on-demand by Roy Atkinson on "Measurement, Management, and Money"